I have supervised two PhD students over my career, which was more than enough. But don’t we need more highly educated individuals? I would argue no, and here’s why. Unfortunately there are just too many PhDs out there. There just aren’t enough academic-related jobs out there for the oversupply of PhDs.

But you say PhDs could work in industry? Sure some could, but the reality is that people with doctoral degrees are often (a) overqualified in a narrow field of expertise, and (b) not trained to work in anything but academia. It’s easy to become overqualified. No company is going to hire a handful of PhDs in computer science, certainly not when they can hire people with a basic degree and 6-8 equivalent years of experience. Just because someone has written a thesis on some esoteric aspect of AI, does not mean they can actually design or implement a large-scale AI system. There is no barrier to someone with experience being able to deign an AI system, none what-so-ever. So people are actually paying for a piece of paper. And most people who get a PhD want to work in academia – in Nature’s 2019 PhD survey 56% of respondents said that academia is their first choice for a career. Just under 30% chose industry as their preferred destination.

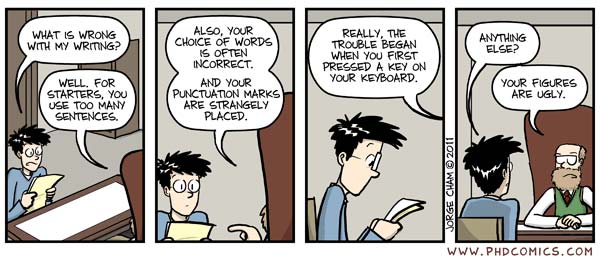

Academia generally trains people for academia, not the greater world of industry, or even government jobs. The emphasis is on research and writing papers, not things like management, and other organizational things. They don’t even teach people how to teach (which is somewhat ironic). Teaching is something people learn as a side-gig, teaching the odd class as a sessional. That’s not to say that people with PhD’s don’t find work in industry, they do. Of the five individuals that worked in our computer systems engineering lab at RMIT, I’m the only one that ended up in academia – the rest have had successful industry careers, but few work in the exact topic they did their research in. But a PhD two decades ago was more likely to get you an academic job.

A 2021 article in University Affairs, described the contradiction between PhD’s and career prospects. Between 2002 and 2017 the number of PhDs graduated in Canadian universities doubled from 3,723 to 8,000. But the number of tenure-stream professors hasn’t changed much – from 36,053 to 45,660 (a 25% increase). This means greater competition for fewer jobs, and non-academic sectors have not increased their uptake. Part of the lack of jobs does stem from university faculty not retiring (due to a lack of mandatory retirement at 65, which ended in Ontario in 2006). In 2016, 14,217 (31%) faculty were in their 50’s and 10,560 (23%) were 60+, so more than half the academics in Canada were over the age of 50. That’s a real problem because there is now a substantial generational gap in many departments. Institutions have made this worse by failing to invest in faculty hires over the last decade. A lack of renewal? Most certainly – the same period the 29 and under group represented a paltry 0.5%. Even the 30’s age group only comprised 14.8%. And that’s a problem.

Ultimately the profusion of PhDs is caused by departments wanting to expand their graduate programs without any regard for employment prospects of graduating students. This is made worse by funding bodies who feel that a majority of grant money should go to paying students – it’s a bit of a vicious cycle. A PhD also does not guarantee better earnings, especially for some STEM fields. According to a 2020 StatsCan survey, a (male) CS PhD has median earnings (2017) of C$98,484, and that’s in the upper echelon. A PhD in statistics sits at C$86,247, and most biological fields are below C$59,275 (that’s below a PhD in history, whose median earnings are C$68,120. Not surprisingly salaries for female graduates are generally lower, which is really quite sad that there are two sets of statistics – so much for equity. For CS this means C$73,678.

The message here is that if you are considering doing a PhD, please look at both job prospects and potential earnings before taking spending 4-6 years doing something you may later regret.

Further reading:

If you are interested in understanding more about PhD life outside academia, I suggest reading “What is life like for PhDs in computer science who go into industry?“, by Vivek Haldar. The main point here may be that in industry, nobody will treat you any different just because you have a PhD. For an insight into the job market, read The post-academic (computer science) job market, by Andrew Mao. An insight into PhD employment is provided in The PhD employment crisis is systemic, by Daniel Roy Torunczyk Schein.